Scammer Kazutsugi Nami

Details |

|

| Name: | Kazutsugi Nami |

| Other Name: | Null |

| Born: | 1933 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | 2009 |

| Age: | 88 |

| Country: | Japanese |

| Occupation: | Businessman |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Investment advisor fraud, mail fraud, wire fraud, money laundering |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | 15 years in prison, forfeiture of US$17.179 billion, lifetime ban from securities industry |

| Known For: | Null |

Description :

The Emperor of Empty Promises: How Kazutsugi Nami Built Japan’s Most Delusional Billion-Dollar Scam

Kazutsugi Nami, born on May 19, 1933, in Mie Prefecture, is a figure whose name has become synonymous with some of the most notorious financial scandals in Japanese history. Over a span of four decades, he built a reputation not for innovation or entrepreneurial brilliance, but for constructing elaborate schemes that preyed on the dreams and vulnerabilities of thousands of ordinary citizens. From pyramid schemes involving car parts and “magic stones” to the bizarre creation of a pseudo-spiritual electronic currency he called Enten, Nami’s story is one of persistent reinvention, relentless manipulation, and delusions of grandeur. His final scam, carried out through his company Ladies & Gentlemen (L&G), lured tens of thousands of investors and eventually cost them the equivalent of billions of dollars. Despite the scale of the damage and the undeniable collapse of his empire, Nami repeatedly insisted that he was a visionary—not a criminal. His eventual arrest in 2009 and sentencing in 2010 marked the end of Japan’s most eccentric and damaging fraud saga, but his legacy continues to serve as a chilling reminder of how charisma, desperation, and unchecked ambition can create financial catastrophes.

Early Life and the Foundations of a Fraudster

Very little is publicly documented about Nami’s childhood, but what is well understood is that by the early 1970s, he had already embarked on a path that blended business, illusion, and deception. His earliest major role came with APO Japan Co., an auto-equipment sales company in Tokyo. Nami rose to the position of vice president, and under his leadership, the company aggressively promoted a device that supposedly removed harmful exhaust gases from vehicles. This product became the basis for what would eventually be recognized as a massive pyramid scheme. Investors were encouraged to purchase and promote the device under promises of extraordinary sales and returns. APO Japan eventually drew in around 250,000 people, making it a national-scale social problem. The model depended heavily on constant recruitment rather than real product value, and when investor recruitment slowed down, the entire operation collapsed. In 1975, APO Japan went bankrupt, and Nami’s name began circulating as a key figure behind the disaster. Yet, rather than disappearing from public view, he simply shifted his strategy and moved on to new ventures.

The Nozakku “Magic Stone” Scam

In 1973, even before APO Japan had officially collapsed, Nami founded Nozakku Co., a company whose business model was even stranger than his previous endeavor. Nozakku sold what it called “magic stones”—ordinary stones marketed as miraculous devices that could transform regular tap water into natural spring water. This pseudoscientific product appealed particularly to elderly individuals and health-conscious consumers, and Nami demonstrated a remarkable ability to blend marketing theatrics with fabricated scientific claims. For a period of time, Nozakku became wildly successful, generating more than two billion yen annually. However, like APO Japan, the company was built on deception and false promises. Complaints eventually surged, and in 1978, Nozakku collapsed. The Mie Prefectural Police arrested Nami in September of that year on charges of fraud, marking his first official encounter with the criminal justice system. He was convicted and sentenced to prison, yet his time behind bars did little to slow his ambitions or modify his behavior. If anything, it seemed to inspire him to return with bigger, bolder, and more extravagant schemes.

PHC and the Pattern of Repeated Deception

Around the same time he launched Nozakku, Nami established PHC, a company formed to sell pressure cookers. While PHC did not grow to the same scale or notoriety as Nozakku or APO Japan, the company further cemented Nami’s pattern: find a product, exaggerate its capabilities, attract large numbers of customers through deceptive promotional tactics, and abandon the enterprise once it became unsustainable. Each company he founded followed this cycle—mass recruitment, misleading promises, rapid growth, collapse, and public scandal. Yet Nami always managed to reappear with new ideas and a renewed aura of confidence. His charisma and boldness shielded him from long-term scrutiny, especially among older Japanese citizens who valued trust, authority, and long-standing company names.

Reinvention After Prison: The Creation of Ladies & Gentlemen (L&G)

After his release from prison, Nami saw an opportunity for reinvention. In 1987, he founded Ladies & Gentlemen (L&G), a Tokyo-based bedding and health-related goods company. On the surface, L&G looked entirely legitimate. It sold futons, mattresses, and health food products, and for years, nothing about its operations seemed overtly suspicious. The company slowly built a positive reputation among customers, especially older buyers who appreciated its soft-spoken marketing and promises of wellness. Nami benefited from the perception that L&G was a “long-standing, trustworthy business,” a reputation that would later become a critical psychological factor when he began soliciting investments. For almost a decade, L&G remained under the radar—small, stable, and profitable enough to give Nami the credibility he needed to execute his most elaborate scheme yet.

The Birth of Enten: A Virtual Currency Built on Fantasy

In the early 2000s, at a time when Japan was struggling with economic stagnation and a growing elderly population seeking financial security, Nami introduced a revolutionary idea—or so he claimed. He unveiled “Enten,” a quasi-currency whose name combined the Japanese words for “yen” and “heaven.” Enten, according to Nami, was destined to become the future of global finance. He marketed it as a spiritual, economic, and technological breakthrough—a type of electronic money that would soon become legal tender in a post-recession world. Investors were told that Enten would not only retain its value but would increase exponentially, doubling year after year. Beginning in 2001, L&G began accepting investment deposits from the public. Anyone who invested at least ¥100,000 received an equivalent amount of Enten, stored electronically on their mobile phones and usable at L&G’s online mall. Here, consumers could purchase vegetables, clothing, jewelry, and even “immune-boosting” futons. By positioning Enten as a futuristic, self-sustaining economy, Nami attracted tens of thousands of followers, many of whom became emotionally attached to the fantasy he constructed. Promotional events called “Enten Fairs” featured testimonials from enthusiastic participants proclaiming how wonderful their Enten life was. For a time, the scheme created a powerful illusion of prosperity.

Promises of High Returns and the Expansion of the Fraud

What truly drew investors was Nami’s extraordinary financial promise: a guaranteed 36% annual return, far exceeding typical market performance. Those who invested once would receive the same amount of Enten every year, creating the illusion that their money could never disappear. For elderly people seeking stability, this was irresistible. By 2007, more than 37,000 people had invested in L&G’s Enten program. The company’s online marketplace became a hub of activity, not because Enten had real value, but because investors desperately wanted to believe in the myth Nami had crafted. Media reports described L&G investors as a cult-like community, with Nami positioned as a visionary leader. Some investors were convinced that Enten would one day replace currency around the world, and Nami encouraged these beliefs by comparing himself to historical Japanese warlords and claiming he had a divine mission to eradicate poverty from the Earth.

The Collapse: Lawsuits, Panic, and the Fall of L&G

By February 2007, the cracks in the system began to show. L&G abruptly stopped paying cash dividends and began issuing returns exclusively in Enten. This sparked confusion, fear, and eventually outrage among investors. People who had invested their life savings realized they could no longer withdraw their money. Attorneys began filing lawsuits, membership cancellations surged, and the Japanese government finally took notice. In October 2007, Tokyo Metropolitan Police raided L&G headquarters, seizing documents and financial records on suspicion of investment law violations. By November 2007, L&G declared bankruptcy, reporting debts of more than ¥42.3 billion. The fantasy world that Nami had created collapsed overnight, leaving tens of thousands of devastated investors in its wake. Elderly victims sold homes, drained savings accounts, and lost assets accumulated over decades of hard work. Some victims blamed themselves for being gullible; others expressed devastation and humiliation. Yet even in the midst of chaos, Nami insisted that he was a victim—not a villain.

Nami’s Delusional Defiance and Public Statements

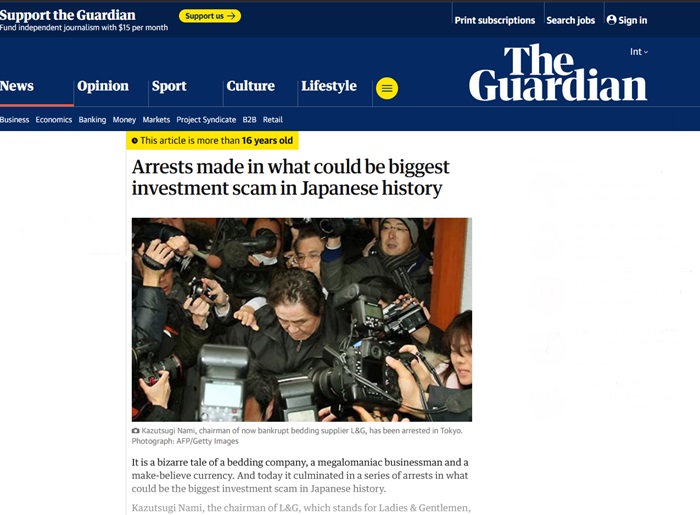

Throughout the scandal, Nami maintained an unwavering—and often delusional—confidence in his ideas. In the weeks leading up to his arrest, he posted rambling blog entries claiming police persecution and insisting that major newspapers were conspiring against him. He argued that Enten was still destined to become global currency within a few years. The morning of his arrest became an iconic media moment in Japan. At 5:30 a.m. on February 4, 2009, police entered a Tokyo restaurant where Nami was having breakfast and drinking beer. Surrounded by reporters, he remained flamboyant and defiant. He famously declared, “Please shoot the face of the biggest conman in history,” even as he denied responsibility for the losses suffered by his followers. When asked if he felt remorse, he responded, “Why do I have to apologize? Nobody lost more than I did. High returns come with high risks.” His statements shocked the nation and showcased a blend of narcissism, denial, and theatrical arrogance.

The Arrest and Charges

On February 4, 2009, police officially arrested Nami and 21 L&G executives for violating the Law for Punishment of Organized Crimes. Prosecutors alleged that between 2001 and 2009, Nami had defrauded investors of at least ¥126 billion (approximately $1.4 billion). Some estimates put the total loss as high as ¥226 billion, which would make the Enten scandal the largest investment fraud in Japan’s post-war history. The arrest confirmed what investigators had suspected for years: L&G was a massive Ponzi scheme, relying entirely on constant recruitment and investor deposits rather than genuine business operations.

Trial, Sentencing, and Public Reaction

Nami’s trial was closely followed by the Japanese media, which had already dubbed him “Japan’s Madoff.” Prosecutors presented overwhelming evidence of deception, financial mismanagement, and deliberate manipulation of vulnerable investors. On March 18, 2010, the Tokyo District Court sentenced Nami to 18 years in prison, one of the harshest penalties ever given for financial fraud in Japan. Victims expressed mixed emotions—some relief that justice had been served, others heartbreak at the loss of their life savings. Many elderly investors would never financially recover. The court described Nami as a manipulative individual who exploited trust, used pseudoscience to lure victims, and demonstrated no remorse.

Legacy and Impact on Japan’s Financial Landscape

The Enten scandal forced Japan to reevaluate its regulations surrounding cryptocurrency-like systems, electronic money, and multilevel investment programs. It also highlighted the vulnerabilities of older citizens who, isolated from traditional financial education or seeking stability in uncertain economic times, were easily swayed by charismatic figures offering unrealistic promises. In retrospect, Nami’s behavior revealed a man driven not only by greed but also by grandiose fantasies. His comparison of himself to samurai warlords, his claims of divine missions, and his predictions that Enten would become world currency suggest a psychological dimension beyond ordinary fraud. Yet for his victims, such speculation offers little comfort. The damage was real: billions of yen vanished, lifelong savings evaporated, and trust in financial institutions weakened. Today, Nami remains a stark symbol of how unchecked ambition and charismatic deception can create economic tragedies.