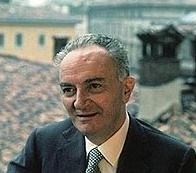

Scammer James Michael Nicholson

Details |

|

| Name: | James Michael Nicholson |

| Other Name: | Nicholson |

| Born: | 1966 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | Alive |

| Age: | 55 |

| Country: | American |

| Occupation: | Entrepreneur |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Ponzi Scheme |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | 40 years in prison |

| Known For: | |

Description :

The Billion-Dollar Illusionist: Inside James Nicholson's Calculated Financial Betrayal

James Michael Nicholson, born in 1966, became one of the most striking examples of how ambition, deception, and financial pressure can converge into a devastating Ponzi scheme that misled hundreds of investors and ultimately destroyed the very empire he spent years claiming to have built. Nicholson presented himself as a successful hedge fund manager, a financial visionary who understood markets better than most and could deliver consistently high returns even during periods of extreme volatility. For nearly a decade, he managed to maintain this façade, creating the illusion that his firm, Westgate Capital Management, was thriving. In reality, the company was hemorrhaging money from the start. Westgate Capital, headquartered in Pearl River, New York, never achieved the level of success Nicholson claimed. Instead, he relied on a web of lies, forged documents, and desperate recruiting of new investors to keep the firm afloat. This illusion finally unraveled in early 2009, when federal investigators revealed the truth behind Westgate's operations, leading to Nicholson's arrest on February 25, 2009. He was ultimately sentenced to 40 years in federal prison, where he remains incarcerated at the Federal Correctional Institution in Otisville, New York. His projected release date is April 7, 2043, meaning he will be 76 years old by the time he completes his sentence.

What makes Nicholson's case particularly compelling is the contrast between the image he crafted and the actual events of his professional life. Before founding Westgate Capital, Nicholson had a notably unstable career trajectory. After graduating from the State University of New York at Stony Brook, he entered the finance world in October 1988 by joining Shearson Lehman Hutton, Inc. His presence there was short-lived, lasting only five months before he transitioned to Drexel Burnham Lambert, another turbulent chapter in his early professional life. But Drexel, too, became merely another stepping stone. Within months, Nicholson moved on once again, this time landing at Smith Barney, where he managed to stay for just over two years. Between 1990 and 1999, Nicholson's résumé expanded with additional stints at Prudential Securities, Merrill Lynch, First Colonial Securities, and The Key Group. These rapid job transitions painted the picture of a man either unwilling or unable to remain grounded within a single institution. Some individuals switch jobs frequently to climb the professional ladder, but Nicholson's pattern suggested something different—unresolved dissatisfaction, inconsistency, or perhaps an inability to make a lasting impact in legitimate financial practice. By 1999, when he left The Key Group to forge his own path, Nicholson had spent more than a decade in the financial world without establishing a significant or stable career identity. Yet this lack of enduring success did not hinder him; rather, it emboldened him to create something entirely new—something that he could control completely.

In 1999, Nicholson co-founded Westgate Capital Management, LLC, in Saddle River, New Jersey, alongside his former SUNY classmate Robert Lee. The firm was positioned as an elite hedge fund manager targeting wealthy individuals who wanted sophisticated strategies tailored to both protect and grow their wealth. Westgate's flagship product, the Westgate Growth Fund, was introduced as an equity long/short strategy that could perform well in all market conditions. From its earliest days, the fund was described as remarkably stable, delivering consistently strong returns regardless of market performance. These returns, which appeared too good to be true, were exactly that—fabricated and strategically marketed to attract new capital. Hedge funds often experience fluctuations in performance due to market volatility, but Nicholson reported astonishingly smooth performance figures year after year. This consistency, combined with his charismatic marketing style, drew the attention of affluent investors who believed they had found a rare financial genius capable of delivering steady profits while others struggled.

Marketing was Nicholson's strongest skill. He had an uncanny ability to communicate confidence, stability, and exclusivity. Investors frequently described him as persuasive, eloquent, and able to make complex financial strategies sound simple and accessible. He fostered a sense of privilege, making clients feel that they were part of an elite circle receiving access to high-value investment opportunities unavailable to the general public. One of his most frequent claims was that Westgate Capital's assets under management exceeded $750 million. The truth, which emerged during the federal investigation, was that the firm never managed more than roughly $218 million—a staggering gap designed to inflate the firm's perceived success and credibility. To strengthen the illusion, Nicholson relied heavily on fabricated performance reports, doctored investor statements, and fake audit documents that gave Westgate the appearance of being a professionally regulated firm.

In December 2008, only months before his arrest, Nicholson aggressively pushed a new investment opportunity on long-time Westgate clients. He promoted what he described as a "special short-term program" offering guaranteed returns of 8 to 10 percent within a single month, but only for Westgate's "best clients." The offer was designed to appear exclusive, reinforcing the idea that Nicholson was rewarding loyalty with insider-level access to extraordinary financial opportunities. At least one investor eagerly added more capital based on this pitch. However, the reality behind this push was far more desperate. By late 2008, Nicholson's Ponzi scheme was running out of new money. The global financial crisis had triggered widespread investor panic, causing clients to request withdrawals at an unprecedented rate. Like all Ponzi schemes, Westgate relied on a continuous inflow of new investment capital to fund withdrawals. Once the inflow slowed and requested withdrawals spiked, the system was doomed to collapse.

Several events triggered the downfall of Nicholson's fraudulent empire. The first major crack appeared in December 2008, shortly after the shocking arrest of another infamous fraudster, Bernie Madoff. Madoff's collapse sent shockwaves through the investment world, causing investors nationwide to reevaluate their financial relationships. Individuals who had previously trusted their fund managers without question began demanding verification, audited statements, and assurances that their money was safe. This new wave of skepticism reached Westgate Capital quickly. One of Nicholson's investors, Ray Froimowitz, representing Carrickmore Property & Development Co., LLC, became increasingly suspicious of the unusually consistent returns reported by Westgate Strategic, one of Nicholson's related funds. Froimowitz requested audited financial statements, which Nicholson promised to provide immediately. But days passed, then weeks, and no documents were delivered.

Frustrated and alarmed, Froimowitz decided to take matters into his own hands. On December 26, 2008, he visited the Manhattan address of Havener and Havener, the firm Nicholson claimed had been auditing Westgate's financials since its inception. What he discovered was a pivotal turning point in the unraveling of the scheme. The address—49 East 41st Street—was nothing more than a small, empty space used as a "virtual office." There were no accountants, no staff, and no evidence that Havener and Havener was a functioning audit firm. This discovery was the clearest evidence yet that Nicholson had been lying for years about the legitimacy of Westgate's operations.

As suspicions mounted, Westgate's financial situation deteriorated rapidly. By January 2009, the firm had begun missing rent payments, failing to pay employee salaries, and facing an increasingly desperate liquidity crisis. Investors attempting to withdraw funds were met with bounced checks due to insufficient account balances. Meanwhile, Nicholson continued to dodge inquiries and delay transparency, trying to buy time even as the walls closed in. His attempts failed. Alarmed investors contacted regulatory authorities, leading to intensified scrutiny from both the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Armed with evidence, investigators closed in swiftly.

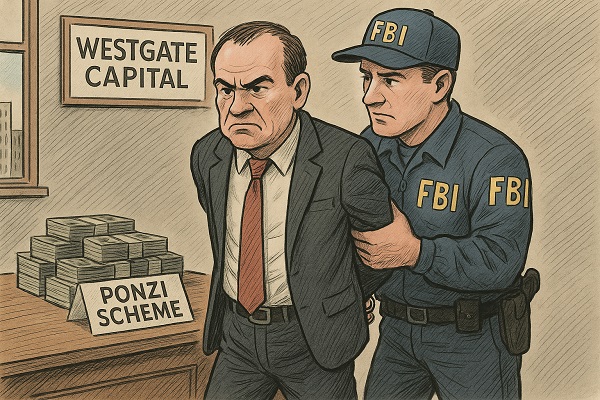

On February 25, 2009, FBI agents arrested Nicholson, marking the dramatic end of Westgate Capital's operations. The U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York charged him with securities fraud, bank fraud, and conducting a massive Ponzi scheme. The SEC simultaneously filed civil charges, stating that Nicholson had misled "hundreds of investors" and stolen millions of dollars through fabricated financial reporting and deceptive practices. Under mounting pressure and confronted with overwhelming evidence, Nicholson eventually confessed to the full extent of his deception. He admitted that Westgate Capital never made money trading. In fact, the firm had been losing money from its earliest days. Faced with mounting losses, Nicholson chose to conceal the truth rather than admit failure. He diverted investor funds to cover trading losses, pay business expenses, and fund his personal lifestyle. Federal investigators discovered that approximately 35 percent of all investor funds were lost through failed trading activity, while another 17 percent was stolen outright for Nicholson's personal use. An additional 6 percent vanished through miscellaneous or untraceable expenses. The remaining funds were shuffled between accounts to maintain the illusion of liquidity and stability when investors attempted to withdraw their money.

The scale of Nicholson's deception was extraordinary. For years, he fabricated performance data, invented audit relationships, and issued falsified account statements to maintain investor confidence. For almost a decade, he successfully concealed the truth by maintaining an elaborate façade supported by new investments. The collapse of Westgate Capital illustrated a classic Ponzi structure: early investors were paid using the contributions of later investors, and the entire scheme depended on a continuous flow of new capital. Once investor withdrawals began outpacing new deposits—particularly during the financial crisis—the scheme became unsustainable.

In 2010, Nicholson pleaded guilty to all major charges. The court, taking into account the magnitude of his crimes, the financial devastation inflicted on hundreds of victims, and the calculated nature of his deception, sentenced him to 40 years in federal prison. This sentence reflects not only the scale of monetary loss but also the profound emotional and psychological harm suffered by investors who trusted Nicholson with their life savings, retirement accounts, and financial futures. Many victims reported that they had believed Nicholson to be a close advisor and a trusted professional, making the betrayal even more devastating.

Nicholson is currently serving his sentence at the Federal Correctional Institution in Otisville, New York, a medium-security facility known for housing white-collar offenders. His projected release date—April 7, 2043—takes into account his inability to qualify for significant early release due to the severity of his crimes. By the time he is released, he will be an elderly man, long removed from the financial world he once manipulated.

The case of James Michael Nicholson stands as a powerful reminder of the dangers inherent in blind trust, unverified claims, and overly consistent investment returns. Investors often assume that hedge funds and private investment firms operate with the same level of oversight as traditional financial institutions, but Nicholson's scheme shows how easily trust can be exploited when regulatory mechanisms are weak and transparency is lacking. His story reinforces the importance of due diligence, independent verification, and skepticism—especially when returns seem unusually stable or guaranteed. Nicholson's downfall echoes many of the same patterns observed in other major financial crimes: the reliance on personal charisma, the misuse of investor trust, the fabrication of documents, and the eventual unraveling once financial pressure becomes too great.

In the broader context of financial fraud, Nicholson's scheme may not have been as large as Bernie Madoff's, but it impacted countless families, individuals, and businesses who believed that Westgate Capital represented safety and financial growth. Instead, they found themselves victims of a calculated lie that lasted nearly a decade. The emotional toll on these investors cannot be understated. Many lost life savings, trust in financial institutions, and a sense of security that may never be repaired. The case serves as an enduring lesson that even the most confident, persuasive financial professional may not be what they appear. For every investor seeking to protect their hard-earned money, Nicholson's story underscores the necessity of asking hard questions, demanding proof, verifying credentials, and maintaining a healthy degree of skepticism in an industry where appearance often masks reality.