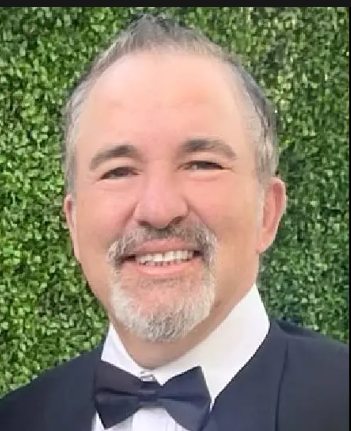

Scammer Anthony Enrique Gignac

Details |

|

| Name: | Anthony Enrique Gignac |

| Other Name: | Prince Adnan Khashoggi, Prince Khalid bin Al Saud |

| Born: | 1970 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 54 |

| Country: | Colombia |

| Occupation: | Con man and Fraudster |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Three counts of wire fraud |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | Several prison terms, most recently 30 years |

| Known For: | Null |

Description :

The Prince Who Never Was: The 30-Year Deception of Anthony Gignac

For more than three decades, a man calling himself Prince Khalid bin Al-Saud lived a life of unimaginable luxury. He traveled by private jet, reclined on yachts, shopped in designer boutiques, wore diamond-encrusted jewelry, owned exotic cars with diplomatic license plates, and entertained wealthy investors in a lavish Fisher Island condominium. He demanded royal protocols, collected extravagant gifts, and promoted exclusive business ventures that promised extraordinary returns.

But none of it was real.

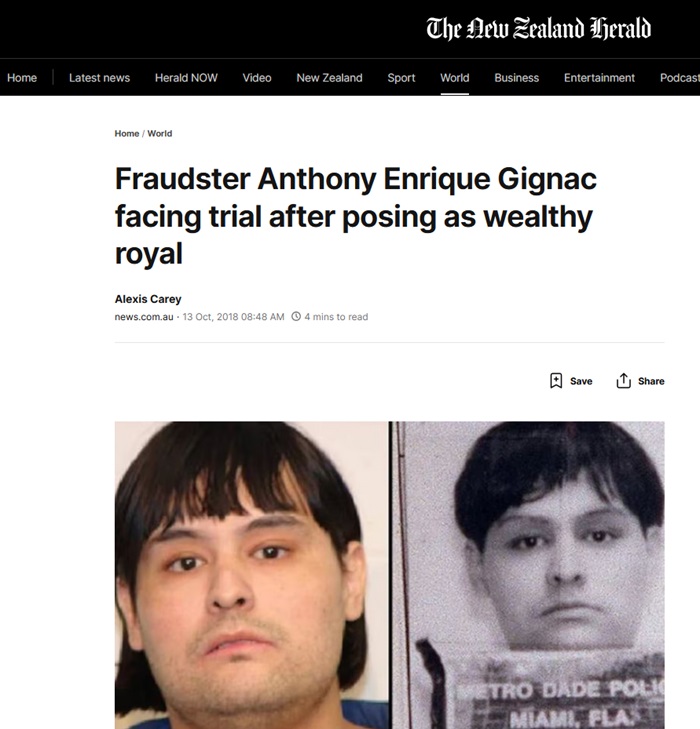

The man behind the royal persona was Anthony Enrique Gignac, a Colombian-born orphan adopted by an American family in Michigan. Far from being a Saudi prince, he was one of the most prolific con artists in U.S. history—an individual who reinvented himself so thoroughly that even seasoned investors, billionaires, and international business figures fell under his spell.

In 2019, after a sweeping federal investigation, Gignac was sentenced to 224 months (18.5 years) in prison by U.S. District Judge Cecilia M. Altonaga. His crimes—spanning wire fraud, aggravated identity theft, impersonating a diplomat, and conspiracy—had stripped investors around the globe of more than $8 million. The spectacular downfall of the self-proclaimed prince exposed not only his elaborate schemes but also the psychological manipulation and charisma that allowed him to deceive so many for so long.

A Troubled Beginning and the Birth of a Persona

Born in Bogotá, Colombia in 1970 as José Moreno, Gignac’s early years were marked by poverty, neglect, and instability. Orphaned at a young age, he survived by begging and stealing food for himself and his younger brother. In 1977, the two were adopted by a Michigan couple and given new names—Anthony and Daniel.

But even in childhood, Anthony exhibited a powerful obsession with wealth and status. At age 12, he convinced a car dealer to let him test-drive a Mercedes by claiming he was the son of a Saudi prince. This early taste of deception would become the template for the next 35 years of his life.

By the late 1980s, he was fully immersed in his royal fantasy. He began calling himself “Prince Adnan Khashoggi,” then evolved to “Prince Khalid bin Al-Saud,” borrowing from real Saudi family names. Hotel staff, retailers, and businesspeople believed him because his confidence was absolute. He lived the role as if it were the truth.

His scams escalated. In 1991, the Los Angeles Times dubbed him “The Prince of Fraud” after he racked up more than $10,000 in unpaid hotel and limousine bills, claiming the Saudi royal family would settle them. It was the first time the alias made headlines, but far from the last.

A Life of Lavish Deception

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Gignac refined his act. He used forged documents, fake diplomatic credentials, and stolen account numbers to secure luxury goods and credit. In one audacious episode, he convinced American Express to issue him a Platinum card with a $200 million credit limit, claiming his father—the king of Saudi Arabia—would be furious if he were denied.

His scams continued through the 2000s, each more elaborate than the last. He extorted expensive gifts, ran up massive hotel bills, and defrauded investors by promising access to foreign princes and royal insiders. When confronted, he fabricated increasingly outrageous stories, including claims of relationships with real Saudi royals. None were true.

Despite repeated arrests—eleven by 2017—he always resurfaced, richer, bolder, and more convincing than before.

Constructing the Perfect Prince

Beginning in 2015, Gignac elevated his fraud to unprecedented heights. He created a fake international investment firm—Marden Williams International (MWI)—with a partner, Carl Marden Williamson. The company promised access to extraordinary deals: European hotels, Middle Eastern jet fuel contracts, Irish pharmaceutical ventures, and even a stake in Saudi Aramco, the world’s most valuable oil company.

To strengthen his royal façade, Gignac crafted an entire world around “Prince Khalid”:

Fake diplomatic license plates, purchased on eBay

Fake Diplomatic Security Service badges for his bodyguards

Saudi-style robes and jewelry, including imitation emeralds and gold

An Instagram account filled with photos of real Saudi royals labeled “my family”

Luxury automobiles—Rolls-Royces, Ferraris, Bentleys—some rented, some borrowed

A two-bedroom condominium on Fisher Island, one of America’s wealthiest enclaves

He insisted that investors follow “Saudi royal protocol”: gift giving, deference, and exclusivity. He traveled with security. He surrounded himself with assistants. He projected power at every turn.

Investors from the United States, Canada, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Hong Kong sent him a combined $8 million, believing him to be a gateway to unimaginable wealth.

None of the money ever went toward actual investments. Every dollar funded Gignac’s extravagant lifestyle.

The Billionaire Who Saw Through the Mask

The scheme began to collapse in 2017, when Gignac attempted his boldest con yet: purchasing a $440 million stake in the world-famous Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach. The hotel’s owner, billionaire Jeffrey Soffer, welcomed the supposed prince with open arms.

For months, Soffer catered to “Prince Khalid.” He gifted him jewelry, offered private jet flights, and entertained him as a potential investor. Gignac responded by flossing wealth on Instagram—private jets, luxury cars, designer sunglasses, and Foxy the Chihuahua riding in a Louis Vuitton dog carrier.

But every con man eventually slips.

For Gignac, the mistake was pork.

During a dinner in Aspen, Soffer watched the self-proclaimed devout Muslim prince order prosciutto—a food forbidden under Islamic law. Suspicious, Soffer hired a private security team to investigate.

The deeper they dug, the more unbelievable the truth became.

Gignac owned nothing he claimed.

His diplomatic plates were fake.

His royal documents were forged.

His “entourage” consisted of paid assistants and actors.

He had no ties to any royal family.

The hotel’s security team turned the case over to the Diplomatic Security Service (DSS), which swiftly uncovered a maze of fraud spanning 30 years and multiple countries.

In November 2017, Gignac was arrested at JFK Airport while returning from a luxury trip to London, Dubai, Hong Kong, and Paris—travel he had funded with investor money and identity theft.

The Long History of a Serial Con Artist

Investigators later discovered that Gignac’s royal impersonation stretched back to the 1980s. His record included:

11 prior arrests for prince-related scams

Fraud convictions in California, Michigan, and Florida

Decades of impersonating royalty for money, gifts, and status

Authorities described him as an extraordinary performer—someone who believed so deeply in his persona that others believed it too.

One investigator later revealed, “He wasn’t playing a role. He lived it.”

Even his counterfeit DSS badges were so convincing that real agents admitted the forgeries were “better than the real thing.”

The Victims Behind the Vanity

Among those caught in Gignac’s orbit was designer Perla Lichi, known for creating palaces for royalty in Qatar and the UAE. Gignac hired her to design a $33 million Fisher Island condominium he claimed to own. He surrounded himself with bodyguards, maids, and lavish displays. He was charming, funny, seemingly generous—and impossibly demanding.

“He was extremely needy,” Lichi recalled. “He could be loving one minute and furious the next.”

She had no idea the prince she was designing for didn’t own the condo, wasn’t Middle Eastern, and wasn’t a billionaire. He was just renting the space—and paying for it with stolen funds.

Others were similarly deceived. Investors believed Gignac’s promises of exclusive energy deals and private wealth opportunities. Luxury retailers trusted his forged credit lines. Even sophisticated business leaders assumed he was authentic.

Conspiracy to commit wire fraud

Judge Altonaga sentenced him to 18 years and 8 months, noting that he had “victimized people for decades” and posed as royalty to manipulate and exploit the wealthy and vulnerable alike.

At sentencing, Gignac addressed the court:

“The entire blame of this operation is on me. I am not a monster.”

But his victims felt otherwise. Many had lost life savings. Others felt humiliated. Some struggled with shame and fear after realizing how deeply they had been manipulated.

The restitution hearing was scheduled to determine how, or if, the stolen millions would ever be recovered.

A Career of Audacity, a Legacy of Deception

Even prosecutors marveled at Gignac’s skill.

His schemes were so outrageous that CNBC devoted an episode of American Greed to his crimes, calling it “The Fake Prince’s Royal Scam.”

One DSS agent recalled a disturbing encounter during a search of Gignac’s condo. A 10-year-old boy approached him and asked:

“Are you a DSS agent? The prince upstairs has DSS agents.”

Even children were drawn into the illusion.

The Lesson Behind the Prince

The story of Anthony Gignac is more than a tale of greed and deception—it is a reflection of how easily charisma, confidence, and appearances can override logic. In an age of social media highlight reels and curated personas, the power of perceived wealth can cloud even the sharpest judgment.

Gignac lived the role so convincingly that the line between his fantasy and reality disappeared—not just for others, but for himself. His downfall is a reminder that illusions flourish when people stop asking questions and start believing what they want to see.

His fraud may have ended with a prison sentence, but the legacy of “Prince Khalid” remains one of the most astonishing cons of the modern era—a story where wealth was an illusion, trust was currency, and the world learned that even a prince can be a lie dressed in diamonds.