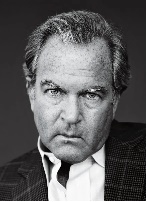

Scammer Albert Gonzalez

Details |

|

| Name: | Albert Gonzalez |

| Other Name: | soupnazi, segvec |

| Born: | 1981 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 43 |

| Country: | Cuba |

| Occupation: | Computer Hacker |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Credit Card Theft, Hacking |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | 20 years federal prison |

| Known For: | Hacking |

Description :

Codes of Silence, Codes of Crime: Inside the Informant Culture and the Cyber Empire of Albert Gonzalez

An informant—often called an informer, snitch, rat, stool pigeon, stoolie, tout, or grass—is a person who provides privileged or concealed information, often incriminating, about individuals or organizations to authorities or investigative bodies. This information is typically confidential and relates to activities that are illegal, unethical, or otherwise hidden from public knowledge. In the realm of criminal investigations and law enforcement, informants are officially categorized as Confidential Human Sources (CHS) or Criminal Informants (CI). These individuals serve as conduits between hidden worlds and institutions of power, enabling officers to gain insights into criminal enterprises that would otherwise remain inaccessible. In politics, industry, entertainment, academia, and even within government agencies, informants play a sometimes controversial role—viewed as heroes by some, traitors by others. Their influence extends far beyond courtrooms and criminal organizations, shaping outcomes in labor disputes, political movements, and even global intelligence operations.

The Role of Informants in Law Enforcement

In modern policing, informants are indispensable. They contribute significantly to solving homicides, disrupting drug networks, preventing gang violence, and uncovering corruption. Any citizen who provides crime‐related information is technically an informant, though the term typically evokes individuals who operate inside criminal groups. Law enforcement agencies often use informants to gather intelligence that officers cannot obtain through surveillance or conventional investigative methods. However, this dependence creates ethical and legal dilemmas. Some informants receive leniency for their own crimes, sometimes to the frustration of victims or prosecutors. Others fabricate stories to obtain benefits, causing wasted resources or wrongful convictions. Yet police departments worldwide continue to rely on informants because they offer something no tool or technology can replace: firsthand, internal knowledge of criminal behavior.

Betrayal and Danger: The High Cost of Cooperation

Within criminal circles, informants face extreme risk. They are viewed as traitors, and betrayal is often punished harshly—with beatings, torture, or execution. Because of this, informants must be protected. Many receive new identities, relocation assistance, or entry into witness protection programs. Those incarcerated are segregated to avoid retaliatory violence from fellow inmates. The need for secrecy shapes their entire lives, creating a dual identity that can persist long after their usefulness to law enforcement ends. For some, cooperation becomes a path to escape a dangerous lifestyle. For others, it leads to perpetual fear, isolation, and psychological strain.

Why Informants Cooperate: The Motivations Behind Betrayal

Informants rarely act for a single reason. Their motivations typically fall into three broad categories: self‐interest, self‐preservation, and conscience. Under self‐interest, informants may seek financial rewards, reduced sentences, freedom from charges, relocation, removal of rivals, or simple revenge. These incentives can transform a long-time criminal into a valuable asset for prosecutors. Self‐preservation reflects the desire to avoid harm, arrest, or imprisonment, or to obtain entry into witness protection. In many cases, fear drives individuals to cooperate when they feel trapped or endangered. Lastly, some informants act from conscience. They may feel guilt for past actions, desire redemption, hope to leave a criminal lifestyle, or genuinely wish to assist society. Although less common, conscience-driven informants have historically played significant roles in exposing corruption, organized crime, and political abuses.

Informants in Labor Movements, Politics, and Social Causes

Beyond criminal investigations, informants have shaped economic and political movements for centuries. Corporations, particularly in the early 20th century, employed labor spies to infiltrate unions, report on worker organizing efforts, sabotage strikes, and undermine collective bargaining. These spies were sometimes trained detectives or coerced employees who betrayed their colleagues under pressure. In politically charged environments, government agencies deployed informants to weaken activist movements, civil rights organizations, and antiwar groups. These infiltrations caused internal distrust, fragmentation, and in some cases, wrongful arrests. Informants also played roles in exposing government corruption. In some nations, whistleblowers are financially rewarded with a percentage of recovered funds when their information leads to the prosecution of corrupt officials. Historically, however, the use of informants has not always aligned with justice. The Roman historian Lactantius described a case where a coerced informant provided false testimony against innocent women, only to later confess the truth on his deathbed—showing the dangerous consequences of manipulation and torture.

Jailhouse Informants and the Crisis of Reliability

One of the most controversial categories of informers is the jailhouse informant—prisoners who claim to have overheard confessions from other detainees. In exchange for testimony, they may receive reduced sentences, dropped charges, or special privileges. Their accounts, however, are notoriously unreliable. Studies by the Innocence Project reveal that false testimony from jailhouse informants contributed to 15% of wrongful convictions later overturned by DNA evidence and 50% of wrongful murder convictions. High-profile cases involving Stanley Williams, Cameron Todd Willingham, Thomas Silverstein, Marshall “Eddie” Conway, Temujin Kensu, and the suspect in the Etan Patz disappearance highlight how easily the justice system can be corrupted by incentivized lies. Yet prosecutors still use jailhouse informants because their testimonies can sway juries—especially in cases with limited evidence. This practice continues to spark national debate on ethics, reform, and the reliability of criminal justice procedures.

The Early Life of Albert Gonzalez: From Curious Teen to Obsessive Hacker

Understanding informants helps set the stage for one of the most dramatic informant‐criminal stories of the digital age: the rise and fall of Albert Gonzalez, one of the most infamous hackers in U.S. history. Gonzalez’s path began innocently enough. Born to Cuban immigrants in Miami, he grew up in a modest, hardworking household. His father operated a landscaping business, and his mother maintained a traditional family environment. At age 12, Albert purchased his first computer, setting in motion an obsession that would soon dominate his life. Unlike many young computer enthusiasts, Gonzalez’s fascination escalated sharply when his machine contracted a virus. Rather than panicking, he became fixated on understanding how it worked, how to defend against it, and why someone would create such a malicious tool. This curiosity transformed into obsession. His grades declined, his social interactions withered, and he spent countless hours isolated in front of a glowing screen. His mother urged him to seek psychological help, while his father—desperate to intervene—once enlisted local police officers to stage a mock arrest. Yet nothing stopped him.

The Teenage Hacker Who Breached NASA

By age 14, Albert Gonzalez had moved far beyond innocent experimentation. Using stolen credit card numbers from online forums, he purchased video games, clothing, and electronics. Then came an audacious achievement: hacking into NASA’s computer systems. Though extraordinary for a teenager, this was not entirely unprecedented—other young hackers had performed similarly bold attacks. Still, the breach caught the attention of federal authorities. FBI agents visited his high school and invited the boy, his father, and their lawyer to the Miami field office for questioning. After a lengthy interview, agents concluded that Gonzalez was talented and knowledgeable but not malicious enough to prosecute. They offered a deal: no charges would be filed if his parents confiscated his computer for six months. The family agreed. For most teenagers, such a brush with federal law enforcement would create enough fear to halt dangerous activities forever. But when Gonzalez regained access to a computer, he returned to hacking with greater intensity than before. This moment revealed a defining truth about his personality: logical consequences could not overcome deep-rooted obsession.

The “Keebler Elves”: Early Mischief and Growing Skills

During his teenage years, Gonzalez joined a hacker group calling themselves the “Keebler Elves.” Their activities included website defacements, pranks, and low-level intrusions into government systems. They hacked the Indian government’s website and replaced content with offensive jokes. They broke into the Storm Prediction Center’s site and left messages proclaiming their power. While irritating and technically illegal, these attacks were more juvenile mischief than organized crime. But Gonzalez’s hacking interests soon expanded. When he realized that compromised websites often contained stored credit card information, he began monetizing his skills. He had stolen merchandise shipped to vacant houses, retrieving packages during school breaks with the help of friends. This ability to profit—combined with his growing technical knowledge—pulled him deeper into cybercrime. He became increasingly adept at masking his identity, exploiting vulnerabilities, and understanding system architectures.

The Making of a Cybercriminal: Young Adulthood and Skill Expansion

After graduating high school, Gonzalez briefly attended community college before dropping out. He secured jobs in tech roles—including at a New Jersey internet service provider—by hacking into their systems and then convincing them to hire him. His employers had no idea they were recruiting one of the most capable hackers in the country. Yet while he led an outwardly calm and conventional life among elderly neighbors in New Jersey, he spent nights honing his cybercriminal skills.

This period marked his entry into ShadowCrew, one of the earliest and most influential cybercrime forums in the world. Under the alias “CumbaJohnny,” he became a central figure in a marketplace that sold stolen credit card data, forged passports, fake driver’s licenses, counterfeit Social Security cards, and other illegal goods. ShadowCrew was both a criminal enterprise and a community—a precursor to today’s dark web markets. Gonzalez became a site administrator, overseeing millions of stolen card numbers and facilitating transactions between criminals worldwide.

The First Arrest: From Hacker to Secret Service Informant

In July 2003, Gonzalez’s double life collapsed during a nighttime ATM scam in Manhattan. Wearing a long black wig and fake nose ring, he attempted to withdraw thousands of dollars using encoded debit cards. A plainclothes NYPD detective observed his suspicious behavior and arrested him. The Secret Service—responsible for investigating financial cybercrimes—immediately recognized him as a major target linked to ShadowCrew. Facing enormous charges and potential decades in prison, Gonzalez accepted a surprising deal: he would work as an informant for the U.S. Secret Service.

The agency offered him stability, protection, treatment for drug addiction, living expenses, and a $75,000 salary. Gonzalez accepted. Agents later said he became a valued partner—soft-spoken, intelligent, articulate, calm, and exceptionally skilled at explaining the inner workings of cybercrime. His insights led to arrests worldwide and the dismantling of ShadowCrew during “Operation Firewall,” one of the biggest cybercrime takedowns of its era. For a brief time, Gonzalez seemed rehabilitated. He gained weight, dressed better, quit drugs, and became close with the agents who nicknamed him “Soup,” after his earlier online persona “SoupNazi.”

The Return to Crime: A Double Life Reborn

But the logic of redemption could not override the depth of Gonzalez’s obsession. Even while assisting the Secret Service, he secretly reentered cybercrime. Along with accomplices, he began conducting more sophisticated hacks targeting retail giants such as TJX Companies, BJ’s Wholesale Club, OfficeMax, Barnes & Noble, Boston Market, and eventually Heartland Payment Systems—the largest theft of credit card data in U.S. history. Using SQL injection, ARP spoofing, and wireless network penetration, Gonzalez and his team stole more than 130 million credit and debit card numbers, costing retailers, banks, and insurers hundreds of millions of dollars. Gonzalez personally accumulated luxury vehicles, jewelry, cash, and gifts for his girlfriend. Yet even as he lived lavishly, he worked daily alongside federal agents who believed he had abandoned crime.

Massive Breaches and the Collapse of Trust

The TJX breach alone compromised 45.6 million cards. The Heartland breach exposed the vulnerabilities of entire financial systems, prompting nationwide reforms. Gonzalez operated globally, storing data on Russian servers, communicating with international hackers, and refining techniques for large-scale corporate infiltration. His operations transformed cybercrime from scattered attacks into organized, industrialized theft. Meanwhile, the Secret Service—unaware of his deception—praised him as a model informant. But the illusion unraveled when investigators traced massive breaches back to the same techniques he had once taught agents to recognize. The betrayal stunned law enforcement. Gonzalez had used his insider knowledge to evade detection and exploit weaknesses in the very investigative systems he helped build.

Arrest, Conviction, and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

Gonzalez was finally arrested in 2008 after hacking the Dave & Buster’s restaurant chain. During searches, authorities found $1.6 million hidden in his parents’ backyard, along with weapons, laptops, and extensive criminal evidence. In court, he faced multiple indictments for wire fraud, computer intrusion, and financial crimes. Ultimately, he pleaded guilty and received a 20-year federal sentence, one of the harshest ever imposed for cybercrime in the United States. He forfeited luxury vehicles, a Miami condominium, jewelry, cash, and millions in assets. His defense claimed that he suffered from Asperger’s syndrome and had been manipulated by authorities, but courts rejected these arguments. While incarcerated, Gonzalez continued to insist that he had been acting partly as a government informant. Despite this, the legal system held him accountable for orchestrating the largest credit card data theft in history.

Legacy of a Cybercriminal and Lessons on Informant Culture

Albert Gonzalez’s story is a cautionary tale about brilliance without boundaries, obsession without restraint, and the dangerous duality of informants embedded in criminal spheres. His case forced corporations, financial institutions, and government agencies to reform cybersecurity protocols. He became a symbol of how one individual—talented, disturbed, and driven—could undermine the technological infrastructure of an entire nation. After his release in 2023, Gonzalez remained a controversial figure. Some view him as a cyber genius who lost control, others as a manipulative criminal who exploited both hackers and law enforcement. His actions cemented his place in history as one of the most prolific cybercriminals ever exposed.

At the same time, his story exposes the complexities of informant use. Informants can dismantle criminal organizations—but they can also deceive, manipulate, and exploit the system. Gonzalez perfectly embodied both sides of the informant world: a cooperative insider who helped federal agents, and a deeply embedded criminal who used his privileged access to commit even greater fraud.

Through the intertwined lenses of informant culture and cybercrime, the saga of Albert Gonzalez reveals uncomfortable truths about secrecy, power, and human motivation. Informants occupy a gray zone where loyalty and betrayal coexist, where justice intersects with self-preservation, and where systems meant to uphold order can be manipulated by those determined to break them. Gonzalez’s life illustrates how obsession can override reason and how one person’s choices can reshape entire industries. In examining the hidden world of informants and the rise and fall of a digital criminal empire, we gain insight into the vulnerabilities of both human nature and the technological systems we rely on every day.