Scammer Chaelie Javice

Details |

|

| Name: | Chaelie Javice |

| Other Name: | Null |

| Born: | 1993 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 31 |

| Country: | American |

| Occupation: | Former CEO of Frank |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Wire fraud, money laundering, conspiracy |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | $2 million bond |

| Known For: | CEO of Frank |

Description :

United States v. Charlie Javice: Inside the $175 Million Frank Acquisition Fraud

The criminal case against Charlie Javice represents one of the most consequential fintech fraud prosecutions in recent years and serves as a stark warning about the dangers of deception in high-stakes corporate acquisitions. Javice, once celebrated as a young entrepreneur seeking to simplify the financial aid process for students, ultimately orchestrated a calculated and sustained scheme to mislead JPMorgan Chase into purchasing her startup, Frank, for $175 million. The fraud relied on inflated customer numbers, fabricated datasets, and deliberate misrepresentations that went to the very core of the transaction’s valuation. When U.S. District Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein sentenced Javice to 85 months in federal prison, the judgment brought closure to a case that revealed how ambition, credibility, and insufficient verification can converge to produce catastrophic outcomes, even for the world’s most sophisticated financial institutions.

Early Life, Education, and Entrepreneurial Aspirations

Charlie Javice emerged from elite academic institutions with an early reputation for intelligence, determination, and ambition. She graduated from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, a credential that placed her among the most promising young business leaders of her generation. Javice often framed her entrepreneurial ambitions around social impact, citing her personal frustration with the complexity of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA. The FAFSA form, which students must complete to apply for federal financial aid, is widely regarded as confusing and burdensome, particularly for students from lower-income families. Javice positioned herself as someone uniquely motivated to solve this problem, blending commercial opportunity with public benefit.

Her narrative resonated strongly with investors and the media. Javice became a visible figure in fintech discussions, appeared on major news outlets, and was eventually named to Forbes’ “30 Under 30” list. These accolades reinforced her public image as a socially conscious innovator and helped establish trust in her leadership and claims.

Founding of Frank and Its Business Model

In or around 2017, Javice founded Frank, a for-profit startup designed to help students complete the FAFSA more easily. Frank marketed itself as a technology-driven solution that could streamline the application process, reduce errors, and help students maximize their financial aid eligibility. While FAFSA itself is available for free, Frank charged users hundreds of dollars for assistance, presenting its services as an investment in a student’s educational future.

Javice served as Frank’s chief executive officer and public spokesperson. Olivier Amar joined as the company’s Chief Growth Officer and effectively became its second-in-command. Together, they promoted Frank as a rapidly growing platform with significant market penetration among college-bound students. The company’s marketing emphasized both its purported impact and its scale, suggesting that Frank had reached millions of users nationwide.

Early Scrutiny and Regulatory Concerns

Even before the company’s sale to JPMorgan, Frank attracted regulatory attention. In 2018, the company reached a settlement with the federal government over allegations that it had misrepresented its connection to the U.S. Department of Education. Later, during the COVID-19 pandemic, members of Congress raised concerns that Frank was misleading students by promoting what appeared to be nonexistent or exaggerated relief programs. Although these issues did not result in criminal prosecution at the time, they raised early red flags about the accuracy of Frank’s public claims and marketing practices.

Despite these warning signs, Frank continued operating and expanding its public profile. Javice’s credibility, reinforced by her media presence and investor backing, helped the company maintain momentum and avoid deeper scrutiny.

The Decision to Sell Frank and JPMorgan’s Interest

By 2021, Javice began actively pursuing the sale of Frank to a larger financial institution. Two major banks entered acquisition discussions, including JPMorgan Chase. For JPMorgan, the appeal of Frank lay not only in its stated mission but also in the value of its alleged customer base. Executives testified that they believed Frank had amassed millions of young users who could be marketed banking products over the course of their financial lives.

During negotiations, Javice repeatedly represented that Frank had approximately 4.25 million users. She explicitly defined these users as individuals who had signed up for Frank accounts and for whom the company possessed key identifying information, including names, email addresses, and phone numbers. These representations were critical to JPMorgan’s valuation of the company and its willingness to proceed with the acquisition.

In reality, Frank had approximately 300,000 users who met these criteria. The vast discrepancy between the claimed and actual user base formed the foundation of the fraud.

Due Diligence Pressure and Fabrication of Data

As JPMorgan progressed through its due diligence process, it sought verification of Frank’s user numbers and the quality of the associated data. This request posed a serious obstacle for Javice and Amar, as accurate verification would have exposed the inflated claims. Rather than correcting the misrepresentations, they chose to escalate the deception.

Javice and Amar first approached Frank’s director of engineering and asked him to create a synthetic dataset that would appear to represent millions of users. The director raised concerns about the legality of the request, prompting Javice to acknowledge the risk by stating, in substance, that she did not want anyone to end up in “orange jumpsuits.” The director refused to comply.

Undeterred, Javice hired an external data scientist and paid him approximately $18,000 to generate millions of fake names and associated data. This synthetic dataset was then provided to a third-party vendor involved in JPMorgan’s verification process. The vendor confirmed that the dataset contained more than 4.25 million rows, and this confirmation was conveyed to JPMorgan as validation of Javice’s claims.

Completion of the $175 Million Acquisition

Relying on Javice’s representations and the fabricated verification, JPMorgan agreed to acquire Frank for $175 million in late 2021. As part of the transaction, JPMorgan hired Javice and other Frank employees. Javice personally received more than $21 million for her equity stake and was contractually entitled to an additional $20 million retention bonus.

At the time of closing, JPMorgan believed it had acquired a company with millions of engaged users and a valuable dataset that could be leveraged for long-term customer acquisition. In reality, the bank had purchased a company whose central asset—the user base—had been grossly misrepresented.

Post-Acquisition Deception and Purchased Data

After the acquisition, JPMorgan employees requested access to Frank’s user data to begin marketing campaigns. In response, Javice provided data that purported to represent Frank’s customers. Unbeknownst to the bank, this data was not collected by Frank at all.

At or around the same time she was fabricating synthetic data, Javice and Amar had purchased real student data on the open market. They acquired a dataset of approximately 4.5 million students for $105,000 but found that it lacked certain data fields Javice had claimed Frank possessed. To address this, they purchased additional datasets to augment the information. This purchased data, rather than Frank’s actual user data, was ultimately provided to JPMorgan as proprietary customer information.

Discovery of the Fraud and Civil Litigation

JPMorgan eventually uncovered inconsistencies that led it to conclude that Frank’s user data was fraudulent. In December 2022, the bank filed a civil lawsuit against Javice, alleging that she had fabricated millions of user accounts and misrepresented the company’s success. JPMorgan terminated Javice’s employment approximately one month earlier.

Javice countersued, arguing that millions of users had visited Frank’s website to read content related to financial aid. However, she did not dispute that fewer than 300,000 users had actually used the platform to complete FAFSA forms. This argument failed to address the core allegation that she had misrepresented the number of genuine users during acquisition negotiations.

Criminal Charges and Arrest

In early 2023, federal prosecutors brought criminal charges against Javice and Amar, alleging conspiracy, bank fraud, wire fraud, and securities fraud. The Securities and Exchange Commission filed parallel civil charges, asserting that Javice had violated federal securities laws by making false statements to induce JPMorgan into the transaction.

Javice was arrested and released on $2 million bail. She remained free pending trial, residing in Florida and later arguing that pretrial monitoring measures would interfere with her attempts to rebuild her life.

The Federal Trial

The criminal trial began in February 2025 and lasted approximately five to six weeks. Prosecutors presented extensive evidence demonstrating that Javice knowingly and intentionally inflated Frank’s user numbers and fabricated data to support her claims. Key testimony came from Frank’s chief software engineer, who described being asked to create fake data and refusing to do so.

Prosecutors also showed that the third-party verification process relied heavily on data supplied by Javice and did not independently confirm whether the listed individuals were real users. The defense sought to exploit this weakness, arguing that JPMorgan’s due diligence failures contributed to the outcome. The jury ultimately rejected this argument.

Conviction on All Counts

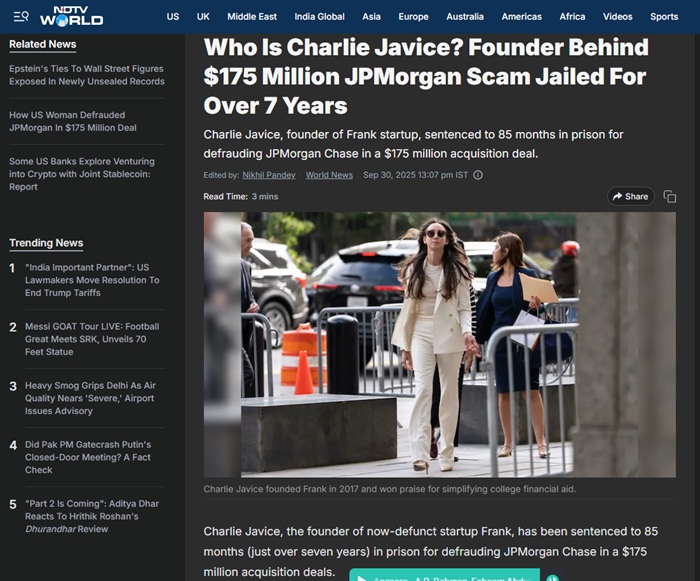

In March 2025, a jury found Javice and Amar guilty on all four counts charged: conspiracy, bank fraud, wire fraud, and securities fraud. Each offense carried a potential sentence of up to 30 years in prison. The verdict drew comparisons to other high-profile startup fraud cases, including Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, and marked a decisive rejection of the defense’s narrative.

Sentencing Proceedings

Federal prosecutors sought a sentence of approximately 12 years, emphasizing the scale, duration, and deliberateness of the fraud. Defense attorneys requested leniency, citing Javice’s age, charitable activities, lack of prior criminal history, and the reputational damage she had already suffered. Supporters submitted letters highlighting her personal qualities and past community service.

Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein acknowledged these factors but emphasized that sentencing must reflect the seriousness of the crime and the need for deterrence.

The Sentence and Financial Penalties

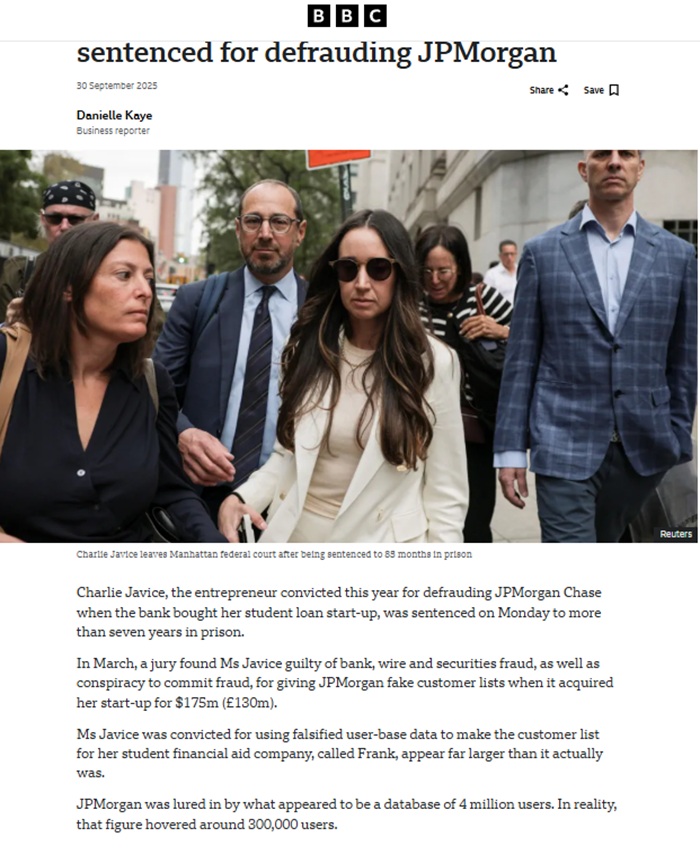

Judge Hellerstein sentenced Javice to 85 months in federal prison, followed by three years of supervised release. He also ordered her to forfeit more than $22 million and to pay more than $287 million in restitution to JPMorgan jointly with Amar. In total, the financial penalties exceeded $300 million.

In delivering the sentence, Judge Hellerstein described Javice’s conduct as a “large fraud” and emphasized that while JPMorgan’s due diligence failures were notable, they did not excuse her criminal behavior.

Broader Implications and Lessons Learned

The Frank case has become a widely cited example of the importance of rigorous due diligence in corporate acquisitions. It highlights how reliance on surface-level verification and competitive pressures can undermine safeguards designed to prevent fraud. The case also reinforces a fundamental legal principle: even early-stage private companies must be truthful in their representations, and fabricated data will be met with severe consequences.

Charlie Javice’s rise and fall illustrate how credibility, ambition, and narrative can be weaponized to deceive even the most powerful institutions. What began as a startup promising to help students navigate financial aid ended with a federal conviction, a lengthy prison sentence, and hundreds of millions of dollars in penalties. The case serves as a lasting reminder that innovation does not excuse dishonesty and that fraud, regardless of how it is packaged, will ultimately be exposed and punished.