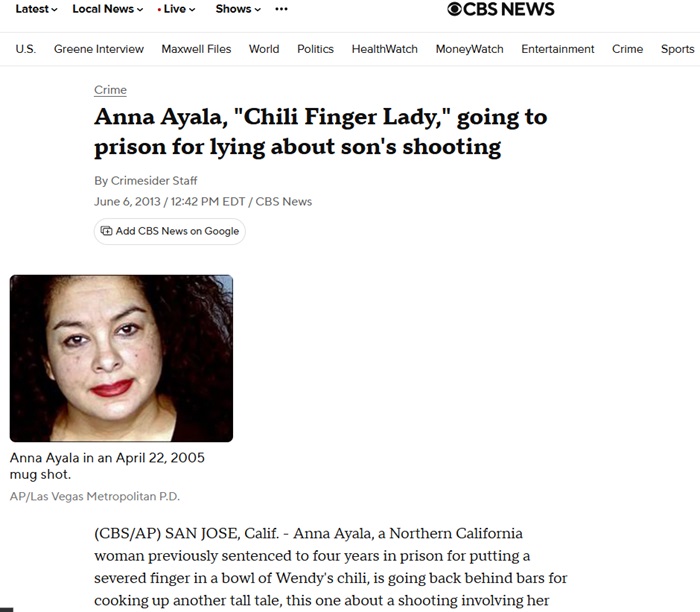

Scammer Anna Ayala

Details |

|

| Name: | Anna Ayala |

| Other Name: | Null |

| Born: | 1965 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 54 |

| Country: | United States |

| Occupation: | Criminal, Hoaxer |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Null |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | Four years in prison |

| Known For: | Null |

Description :

The Woman Behind the Finger: The Legal Fallout and Lasting Infamy of Anna Ayala

Defendant Anna Ayala appeals from a judgment entered after she pleaded guilty to three felony charges: presenting a false or fraudulent insurance claim (Pen. Code, § 550, subd. (a)(1); count 1), attempted grand theft of personal property over $400 (§§ 664, 487, subd. (a); count 2), and grand theft of personal property over $400 (§§ 484–487, subd. (a); count 3). The convictions on counts 1 and 2 stem from the widely publicized 2005 incident in which Ayala reported finding a severed human finger in a bowl of Wendy’s chili. The conviction on count 3 arose from a separate scam involving her fraudulent “sale” of a mobile home she did not own. Ayala also admitted a special allegation attached to counts 1 and 2 that her conduct caused property damage exceeding $2,500,000 (§ 12022.6, subd. (a)(4)).

At sentencing, the trial court imposed the upper term of five years for count 1, plus a consecutive four-year enhancement for the property-damage allegation. For count 2, Ayala received 18 months plus a four-year enhancement, though execution of that sentence was stayed under § 654. She was also sentenced to a concurrent two-year term for count 3. The court further ordered Ayala to pay restitution to Wendy’s International, Jem Management (owner of several Wendy’s locations in Santa Clara County and Fresno), and Jem’s employees.

Ayala raises three issues on appeal. First, she argues that the restitution order requiring payment of $170,604.66 to 177 line employees and nine general managers of Jem was improper under § 1202.4, claiming these individuals were not “direct victims” of her crimes. Second, she challenges the property-damage enhancement (§ 12022.6, subd. (a)(4)), contending that the enhancement was unlawfully based on Wendy’s losses in profits and goodwill, which she asserts do not qualify as “property damage” under the statute. Third, she argues that imposition of the upper term for count 1 violated her Sixth Amendment jury trial rights and Fourteenth Amendment due process rights, asserting that under Blakely v. Washington (2004) 542 U.S. 296 and Cunningham v. California (2007) 549 U.S. 270, she was entitled to a jury determination of any aggravating facts used to justify the upper term.

We hold as follows:

The Jem employees were direct victims of Ayala’s crimes, and the restitution order under § 1202.4 was therefore valid.

Ayala is procedurally barred from challenging the § 12022.6 enhancement because she failed to obtain a certificate of probable cause as required by § 1237.5.

In light of Cunningham, the imposition of the upper term constituted Blakely error, and the error was not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

Accordingly, we reverse the judgment solely with respect to sentencing and remand for resentencing consistent with the requirements established in Cunningham.

Wendy’s “Chili Finger” Hoax: Anna Ayala Comes Clean After Years of Infamy

The bizarre and unforgettable Wendy’s “chili finger” scandal of 2005—one of the most notorious fast-food hoaxes in American history—resurfaced when the woman behind the scheme, Anna Ayala, finally spoke publicly about what really happened. Her confession and later legal troubles paint a complex portrait of deception, consequences, and attempted redemption.

The Infamous Discovery That Shocked the Nation

In March 2005, Ayala claimed she bit into a partially cooked 1½-inch human finger while eating chili at a Wendy’s restaurant in San Jose, California. Horrified customers and national media seized on the story, and Wendy’s became the butt of late-night jokes. The chain ultimately suffered an estimated $21 million in lost business, and local franchise owners reported nearly $500,000 in direct losses.

Ayala quickly filed a claim with the franchise—a first step toward what could have been a lucrative lawsuit. But investigators found inconsistencies early on: the finger showed no signs of being cooked at Wendy’s required 170°F for three hours, and forensic tests found no trace of Ayala’s saliva on the digit. As San Jose Police Chief Rob Davis noted at the time, it was clear the finger had been planted after the fact.

A Chilling Origin Story

The unraveling of the hoax revealed a disturbing truth: Ayala’s husband, Jaime Plascencia, had purchased the severed fingertip from a co-worker in Las Vegas who had recently lost it in an industrial accident. The couple paid the man $100, and later offered him $250,000 to stay quiet.

In a recent interview after her release, Ayala admitted a critical detail she had never publicly revealed:

“I cooked it,” she said.

Ayala described preparing the fingertip in her Las Vegas home before driving it to San Jose, where she placed it in the chili herself.

Legal Consequences and Public Fallout

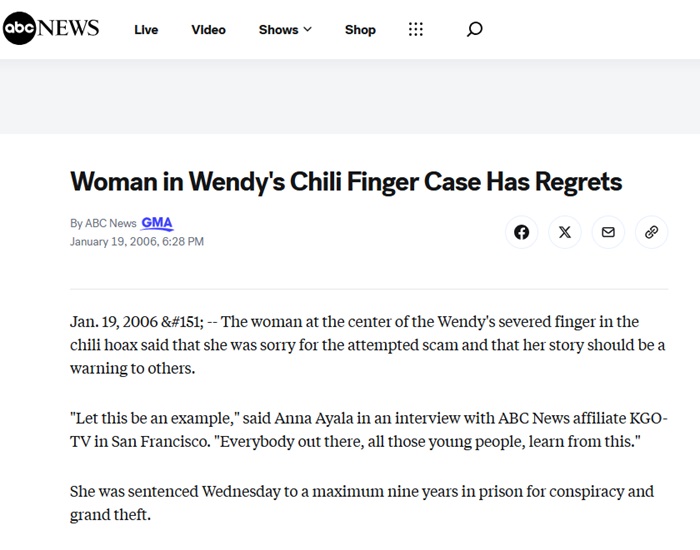

In September 2005, Ayala and Plascencia pleaded guilty to conspiracy to file a false insurance claim and attempted grand theft over $2.5 million. Ayala received a nine-year prison sentence—the maximum she faced—while Plascencia was sentenced to 12 years and four months, partially due to additional unrelated charges, including identity theft and child support violations.

Before sentencing, Ayala tearfully apologized:

“I do take responsibility for my actions… I’m truly sorry.”

Wendy’s employees described the personal toll of the hoax, including reduced work hours and public suspicion. Although a judge ordered Ayala and Plascencia to pay restitution—including roughly $170,000 to affected employees—Wendy’s corporate representatives later stated they would not pursue collection of the millions in losses.

Life After Prison—and More Legal Trouble

Ayala was released after serving four years of her sentence, with a strict condition: she is permanently banned from all Wendy’s locations. Living quietly in San Jose, she initially avoided media attention—until another controversy emerged.

In a new case, Ayala and her son, Guadalupe Reyes, were accused of filing a false police report. Reyes, a convicted felon prohibited from possessing firearms, accidentally shot himself in the ankle. To shield him from legal consequences, they concocted a detailed story involving two supposed attackers—complete with names and descriptions.

Their fabrication was convincing enough that police identified, located, and interrogated an innocent man. Only after Reyes recanted did investigators uncover the truth, leading to misdemeanor charges for both mother and son. Reyes also faces an additional felony charge for illegal firearm possession, while Ayala is being charged as an accessory.

A Legacy of Fabrication

Ayala’s criminal history extends beyond the Wendy’s scandal. Prior to the chili hoax, she had pleaded guilty to defrauding a San Jose woman in a mobile home sale. Combined with her recent false-report case, the pattern has reinforced public skepticism about her attempts at rehabilitation.

Yet Ayala maintains she has learned from the harsh ridicule she endured—both from the public and even prison guards who mocked her infamous crime.

“I learned my lesson and I just want to move on with my life,” she said.

A Notorious Cautionary Tale

The Wendy’s “chili finger” incident remains one of the most memorable corporate fraud cases in modern history—a mix of shock value, investigative twists, and staggering financial damage. For Ayala, who once made headlines around the globe, her story now stands as a stark reminder of how quickly a false claim can spiral into life-altering consequences.