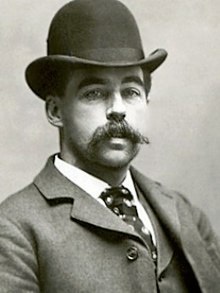

Scammer Angelo Haligiannis

Details |

|

| Name: | Angelo Haligiannis |

| Other Name: | Null |

| Born: | 1967 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 54 |

| Country: | United States |

| Occupation: | President of Hedge Fund |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | Null |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | 15-year jail |

| Known For: | Ponzi scheme |

Description :

The Hedge Fund Mirage: How Sterling Watters Built a Fantasy and Destroyed Real Lives

The story of Sterling Watters begins in the early 1990s with a young man named Angelo Haligiannis, a charismatic member of a Greek immigrant community in Astoria, Queens. Although he enrolled at New York University in 1990, he dropped out in 1993 without completing a degree. His early working life was unremarkable—spent largely in his family’s social circle and at a neighborhood restaurant called Pasta Lovers, where he worked under a family friend. Nevertheless, Haligiannis harbored ambitions far beyond the restaurant business. In 1994, he secured a clerical job at a Merrill Lynch office in Manhattan. Although clerical in nature, this position exposed him to the world of finance and, crucially, connected him with Michael Capul, a broker who later became both his mentor and an essential conduit for funneling investor money into Sterling Watters.

In April 1995, after only thirteen months at Merrill Lynch, Haligiannis left the firm with the stated intention of founding his own hedge fund. Later that year, on November 20, 1995, he formally registered Sterling Watters Group, L.P. in Delaware. He also created Sterling Watters Capital Management, Inc. and Sterling Watters Capital Advisors, LLC, entities that were designated as the general and administrative partners of the hedge fund. These companies formed the organizational backbone of what investors believed to be a sophisticated investment operation. Under the Sterling Watters name, Haligiannis opened accounts with Banc of America Securities, Chase Bank, and at least one offshore account in the Cayman Islands. By early 1996 he began trading, and Sterling Watters was officially presented to clients as an aggressive long–short hedge fund with a strategy blending macroeconomic analysis, fundamental research, and quantitative modeling. The fund boasted a minimum investment of $500,000 and charged the customary 2% management fee and 20% incentive fee, placing itself in the company of elite hedge funds of the time.

Fabricated Success and Manufactured Hedge Fund Glory (1996–1999)

From 1996 onward, Sterlings Watters presented itself as a remarkably successful hedge fund. Quarterly letters—filled with broad market commentary but devoid of specific investment details—reported extraordinary returns that made Sterling Watters appear to be one of the most successful hedge funds in the United States. According to these statements, the fund delivered a dazzling 53.93% net return in 1996, followed by 76.04% in 1997. Even in 1998, a year of modest performance by Sterling Watters metrics, the fund reportedly earned 24.28% net. Then in 1999, as technology stocks soared, Sterling Watters claimed an astonishing 87% net gain.

These results were fabricated. Behind the scenes, there were already glaring warning signs that few investors recognized. Most notably, Sterling Watters never produced a single audited financial statement, despite promising them in its offering documents. Nor was the fund in good legal standing. In 1998, just two years after its formation, Delaware dissolved Sterling Watters Group for failing to pay required corporate taxes. Yet investors continued to pour money into the fund based on its supposed performance and on glowing recommendations by advisers like Capul. Sterling Watters’ reputation grew among a network of wealthy clients, many of whom were not sophisticated institutional investors, but individuals relying on trust rather than due diligence. It was this mix—charisma, fabricated results, and misplaced trust—that allowed the fraud to flourish.

The Human Cost: Investors Drawn Into the Scheme

Among those drawn into Sterling Watters were Susan and Michael Lanzano. In 1994, Susan had begun receiving restitution payments from the German government for property seized from her Jewish grandfather before World War II. The money was a blessing that allowed the family to provide a high-quality education for their son and purchase a summer home in Montauk. With newly acquired financial comfort came the desire for expert investment guidance, which led them to Chase Investment Services and to broker Michael Capul. Capul confidently recommended Sterling Watters, claiming the young hedge fund manager was exceptional and consistently outperformed the S&P 500. Between 2000 and 2003, the Lanzanos invested about $875,000—two-thirds of their savings—believing they were participating in an elite investment vehicle. The truth, however, was that their savings were being siphoned into a collapsing Ponzi-like structure masquerading as a hedge fund.

The Goktekin Family

Another family deeply affected by the Sterling Watters fraud was that of Mehmet and Nurten Goktekin, Turkish-born professionals who moved to the United States seeking opportunity for themselves and their daughters. Mehmet, a licensed pharmacist with a Ph.D. in pharmacology, was referred to Capul during a visit to Chase to inquire about financing a home purchase. The Goktekins quickly came to trust Capul, who advised them not only in personal financial matters but also in choosing a neighborhood and property. In early 1998, trusting his guidance, they invested in Sterling Watters.

Over the next several years, believing the fictional account statements showing spectacular returns, the Goktekins invested ever more heavily—eventually transferring $2.07 million into the fund, including proceeds from the sale of their Australian pharmacy and money collected from relatives in Turkey. The family spent years believing they were wealthy, relying on artificial “distribution payments” to support their living expenses and their daughters’ education. When they attempted to withdraw money in 2004, they encountered excuses, delays, and deception. Ultimately, the Goktekins lost $864,439, and their financial situation deteriorated to the point that Mehmet returned to Australia to work, leaving his family behind in New York.

The Drenis Family and Other Investors

The Drenis family, led by businessman Jerry Drenis, also suffered catastrophic losses. Encouraged by reports of extraordinary returns and reassured by personal interactions with Haligiannis, Drenis invested heavily—culminating in a final investment of roughly $4.89 million in early 2004. When he attempted to redeem funds and received no response, his suspicions grew. Over time, he pressed harder for answers, calling repeatedly, visiting offices, and ultimately preparing to alert authorities. In July 2004, when his attempts to obtain truthful information failed, he brought documentation directly to federal investigators. Drenis was among those whose complaints helped trigger the government’s intervention.

The Reality Beneath the Illusion: Trading Losses and Fictional Performance

Despite its image as a spectacularly successful hedge fund, Sterling Watters was hemorrhaging money from the start. According to SEC filings and subsequent investigations, the fund suffered a devastating $17 million loss in 2000, even while reporting large positive returns to investors. Between 2000 and 2003, additional losses mounted, and by January 2003 the fund’s brokerage accounts held less than $170,000. In truth, the fund had almost entirely ceased trading and had virtually no assets left. Nevertheless, the fund continued to issue quarterly statements showing tens of millions of dollars in fictitious account balances, and marketing materials claimed that Sterling Watters had $180 million under management and had achieved returns of over 1,500% since inception.

This deliberate falsification was the crux of the fraud. Haligiannis used newer investors’ funds to pay earlier investors, to create the illusion of profitability, and to finance his own lifestyle. According to later reports, he purchased luxury vehicles, paid for high-end apartments with rents upwards of $10,000 per month, and made large expenditures at casinos. Some checks drawn on Sterling Watters accounts were even used to acquire gambling chips in Las Vegas. Despite the façade he presented publicly, Sterling Watters was insolvent by 2003.

And Angelo Haligiannis personally

The complaint alleged that since 1996 the defendants had systematically defrauded investors by fabricating returns, distributing false statements, and misrepresenting assets under management. The SEC charged the defendants with violations of securities antifraud provisions, including Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5, and with violations of the Investment Advisers Act.

At the SEC’s request, a federal court immediately issued a temporary restraining order, froze all known assets, ordered expedited discovery, and required a verified accounting from the defendants.

Criminal Prosecution, Guilty Plea, and Fugitivity (2005–2006)

Parallel to the SEC action, federal prosecutors brought criminal charges. In 2004, Haligiannis was indicted on multiple counts, including mail fraud. In September 2005, he pleaded guilty to one count of securities fraud, admitting that he had deceived investors by issuing materially false statements about fund performance and assets.

However, before he could be sentenced, Haligiannis fled. Scheduled to appear for sentencing in January 2006, he failed to appear, triggering an international manhunt. Authorities suspected he might attempt to return to Greece or hide assets overseas. Later reports suggested he had boasted about transferring funds offshore and had accounts in Greece and the Cayman Islands. For several years he remained a fugitive.

Lien Disputes and Court-Ordered Payments (2009)

The distribution of recovered assets proved complicated. Several third parties claimed liens against the funds held by the court. On February 13, 2009, the court issued a Memorandum Opinion and Order settling these claims. Three liens were approved, and the Clerk was directed to disburse $163,861.35 to:

West End Equities, LLC

Marina District Development Co. (Borgata Casino)

Anthony Devito

Subsequent orders clarified that with post-judgment interest, total disbursements to these lienholders would amount to approximately $222,584.67.

The SEC was ordered to file a proposed plan of distribution for the remaining funds, but complications soon arose that prevented immediate compliance.

A Major Obstacle: Lack of Accounting Records (2009–2015)

The SEC informed the court that it could not propose a fair distribution plan because no formal accounting of Sterling Watters’ assets existed. Without knowing each investor’s legitimate net gains or losses—given the fabricated statements and incomplete trading records—it was impossible to determine how to distribute the recovered funds equitably.

At the same time, in a related investor lawsuit, Drenis v. Haligiannis, the overseeing judge ruled that no judgments could be entered until a proper accounting was completed. Both cases were therefore referred to a Magistrate Judge for oversight.

To solve the accounting problem, the court appointed Damasco & Associates LLP as Tax Administrator on September 15, 2009, and then James T. Ashe, CPA, CFFA as Special Master on December 1, 2009, with authority to reconstruct the fund’s records. His fees—capped at $75,000—were paid from the Distribution Fund. Payments to the Special Master were later approved in 2011 and 2012 totaling over $53,000.

After painstaking reconstruction of the fund’s finances, the Special Master filed his report. The related Drenis v. Haligiannis case eventually closed in 2014 and 2015 upon the entry of default judgments, clearing the way for distribution efforts to resume.