Scammer Vincenzo Pipino

Details |

|

| Name: | Vincenzo Pipino |

| Other Name: | |

| Born: | 1943 |

| whether Dead or Alive: | |

| Age: | 78 |

| Country: | Italian |

| Occupation: | |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Charges: | |

| Criminal / Fraud / Scam Penalty: | |

| Known For: | Theft, credit card fraud |

Description :

Stealing Beauty: The Thieves, Tyrants, and Geniuses Who Plundered Art History

Imagine an unlikely dinner party, one where history’s most notorious art thieves and morally ambiguous figures are gathered around a single table. The wine flows freely, conversation is animated, and yet every guest carries a secret past that would make any museum curator uneasy. Sitting together are the man who stole the Mona Lisa, an heiress-turned-revolutionary who made off with a Vermeer, a so-called gentleman thief responsible for thousands of thefts across Europe, and a quiet art dealer whose hands were stained with the greatest cultural plunder in history. To make the evening even more surreal, Pablo Picasso himself takes a seat—an artistic genius whose relationship with stolen art is far more troubling than many admirers care to admit. It is a gathering that blurs the line between criminality, ideology, obsession, and genius, reminding us that the world of art crime is rarely simple and never purely about money.

Rose Dugdale: Heiress, Revolutionary, Art Thief

Rose Dugdale occupies a unique place in the history of art crime, not merely because she was a woman in a male-dominated criminal world, but because her actions were driven less by greed than by ideology. Born into immense wealth, Dugdale was a British heiress and London debutante who seemed destined for a life of privilege. Yet she rejected her aristocratic upbringing entirely, becoming radicalized during the political upheavals of the late 1960s. Influenced by the 1968 student protests and a transformative visit to Cuba, Dugdale embraced revolutionary politics and aligned herself with leftist causes, including civil rights activism and, most controversially, the Irish Republican Army.

Her turn toward militancy culminated in one of the most audacious art thefts of the twentieth century. In 1974, Dugdale participated in a raid on the home of a British Conservative Party politician. Along with her accomplices, she stole nineteen Old Master paintings, works by artists such as Thomas Gainsborough, Francisco Goya, and Peter Paul Rubens. Among the stolen artworks was Johannes Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid, one of the most celebrated paintings in existence. The theft was not intended as a conventional heist. A ransom note was left demanding money for the poor and the release of imprisoned IRA members, framing the crime as a political act rather than simple theft.

The plan failed. Dugdale and her associates were apprehended, and she was sentenced to nine years in prison. Her incarceration was itself historic. She became one half of the first couple to marry while imprisoned in the Republic of Ireland and later gave birth while still in custody. Even after her release, Dugdale did not abandon her beliefs. She continued to advocate for Irish independence, though through political activism rather than violence. Her legacy remains deeply controversial: to some, she is a criminal who endangered cultural heritage; to others, a radical who weaponized art to draw attention to political injustice.

Stéphane Breitwieser: The Thief Who Stole for Love

If Rose Dugdale stole for ideology, Stéphane Breitwieser stole for love—specifically, a deep and obsessive love of art. Between 1995 and 2001, Breitwieser carried out what is arguably the most prolific art theft spree in history. Over six years, he stole approximately 239 artworks from 172 museums across Europe, with an estimated value of $1.4 billion. Traveling largely unnoticed while working as a waiter, Breitwieser targeted small regional museums known for lax security, exploiting the assumption that serious thieves aimed only for famous institutions.

What made Breitwieser truly unusual was his motivation. He did not steal to sell. He never attempted to profit from his crimes. Instead, he kept the artworks for himself, hanging Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces—particularly from the 16th and 17th centuries—in his bedroom. He lived among the stolen art, treating it as a private collection curated purely for personal admiration. This romanticized self-image earned him notoriety, and the Guardian famously called him “arguably the world’s most consistent art thief,” noting that he committed a theft roughly every fifteen days.

Breitwieser’s story took a darker turn after his arrest in 2001, when he was caught attempting to steal a 16th-century bugle from the Richard Wagner Museum in Lucerne, Switzerland. In a misguided attempt to destroy evidence, his mother—who had stored many of the stolen works—destroyed nearly one hundred artworks, throwing paintings into a canal and cutting others into pieces. This irreversible loss shocked the art world. Breitwieser served a three-year prison sentence and later published a memoir titled Confessions d’un Voleur d’art. Despite expressing regret, he was arrested multiple times in subsequent years for additional thefts, suggesting that his compulsion was never fully extinguished.

Kempton Bunton: Theft as Protest

Art theft is not always driven by ideology or obsession; sometimes, it is an act of protest born from resentment. Kempton Bunton was a retired bus driver with a disability, living on a modest income in postwar Britain. His anger was directed not at museums, but at the British government’s insistence that even the poor must pay television licensing fees. That resentment crystallized in 1961 when he learned that the government was willing to spend millions to keep Francisco Goya’s Portrait of the Duke of Wellington in Britain.

Using what he later claimed was insider knowledge about security, Bunton managed to bypass the National Gallery’s alarm system and escape through a bathroom window with the painting. He later sent a letter to Reuters demanding £140,000 to pay television licenses for the poor, along with amnesty for himself. His demands were rejected. Four years later, Bunton returned the painting anonymously and soon surrendered to authorities. In a bizarre legal outcome, he was convicted not of stealing the painting, but only of stealing the frame, which had not been returned.

Bunton’s improbable crime captured the public imagination. Initially dismissed as an unlikely suspect due to his age and disability, he later became a folk hero of sorts. His story inspired cultural references, including a mention in the James Bond film Dr. No and the 2020 movie The Duke. His theft remains one of the strangest examples of art crime motivated by social protest rather than personal gain.

Vincenzo Pipino: The Gentleman Thief of Venice

Among the most legendary figures in European art crime is Vincenzo Pipino, widely known as the “gentleman thief.” Born in Venice in 1943, Pipino reportedly began stealing at the age of eight while working as an errand boy. Over his lifetime, he committed more than 3,000 thefts involving museums, galleries, banks, and private homes. Remarkably, he became the first person to successfully steal from the Doge’s Palace, one of the most heavily guarded historic buildings in Italy.

Pipino’s methods were unusual. Afraid of the dark, he carried out his crimes during the day, blending in with tourists while targeting wealthy residences along Venice’s Grand Canal and Piazza San Marco. An accomplished climber, he accessed properties others deemed unreachable. Pipino cultivated a personal code of conduct, claiming to steal only from the rich and often offering ransoms to allow stolen items to be returned. His crimes were as much about notoriety as profit.

One of his most famous heists occurred in 1991, when he stole Madonna col Bambino from the Doge’s Palace. He returned the painting quickly, having achieved the recognition he desired. However, his criminal career also included drug trafficking and credit card fraud, undermining his gentlemanly image. Over time, Pipino accumulated more than 300 police complaints and served over 25 years in prison across several European countries. Even in retirement, he has stated that he expects to die incarcerated, a reflection of a life defined by crime.

Bruno Lohse: The Art Thief of the Third Reich

While many art thieves steal individual works, Bruno Lohse presided over theft on an industrial scale. A German art dealer and SS-Hauptsturmführer, Lohse played a central role in Nazi art looting during World War II. Acting under Hermann Göring, he became the chief art looter in occupied Paris, overseeing the confiscation of Jewish-owned collections.

Lohse’s work began in 1940 with the cataloging of the vast collection of Alphonse Kann, a prominent French-Jewish art dealer. Kann recovered only a fraction of his collection before his death. Between 1942 and 1944, Lohse supervised the theft of at least 22,000 artworks, selecting the most valuable for Göring and for Adolf Hitler’s planned Führer Museum. After the war, Lohse avoided severe punishment by cooperating with Allied authorities, though the reliability of his testimony has been questioned.

Despite being officially banned from working as an art dealer, Lohse quietly amassed a substantial postwar collection of Old Masters and Expressionist paintings worth millions. His story highlights the uncomfortable continuity between wartime looting and postwar art markets, where stolen works often reentered circulation with minimal accountability.

Vincenzo Peruggia and the Theft of the Mona Lisa

Perhaps the most famous art theft in history was committed not by a master criminal, but by an insider. Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian museum worker, stole Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. He hid in a broom closet overnight, removed the painting from its frame, and walked out of the museum with it concealed under his coat.

The disappearance of the Mona Lisa sparked international panic. The Louvre closed for a week, administrators were fired, and French borders were monitored as trains and ships were searched. A reward of 25,000 francs was offered. Early suspects included avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who in turn implicated his friend Pablo Picasso. Both men were interrogated in open court before being released.

Peruggia remained at large for two years before attempting to sell the painting to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. He claimed patriotic motives, believing the Mona Lisa belonged in Italy. In Italy, he was celebrated as a nationalist hero and served just seven months in prison. Ironically, the theft transformed the Mona Lisa into the world’s most famous painting.

Pablo Picasso and Stolen Inspiration

Picasso’s connection to art theft did not end with false accusations. In 1907, he purchased two ancient Iberian stone heads stolen from the Louvre by Belgian thief Joseph Gery Pieret. It remains unclear whether Picasso commissioned the theft. Fascinated by Iberian art, Picasso kept the statues hidden in his sock drawer, yet openly drew inspiration from them. Their influence is evident in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the painting that launched modernism. When questioned, Picasso returned the sculptures, but the ethical ambiguity of his actions lingers.

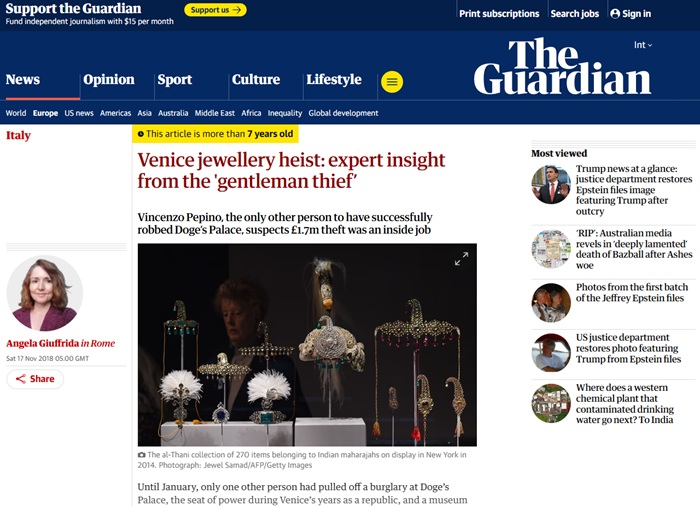

Modern Echoes: Theft at the Doge’s Palace Revisited

The legacy of art crime continues. In a recent theft at the Doge’s Palace, two professional thieves stole jewelry worth millions from a reinforced display case during the final day of an exhibition. The case was opened “like a tin can,” prompting investigations into security failures. Italian police suggested the thieves may have been inspired by Vincenzo Pipino, whose intimate knowledge of the palace once enabled a similarly discreet crime.

Why Art Crime Endures

Art theft persists because art embodies wealth, identity, ideology, and obsession. Whether driven by politics, passion, protest, or power, these crimes reveal as much about human desire as they do about security failures. The dinner table of thieves may be imaginary, but the questions they raise—about ownership, value, and morality—remain very real.