I never imagined that my quiet life would end up inside the records of an international crime syndicate.

I am THE 73-YEAR-OLD JAPANESE RETIREE, and my personal details—my phone number, my bank balance, my private life—were found scattered across the floor of a bombed-out compound in O’Smach, Cambodia. That place wasn’t a hotel. It wasn’t an office. It was a fraud factory.

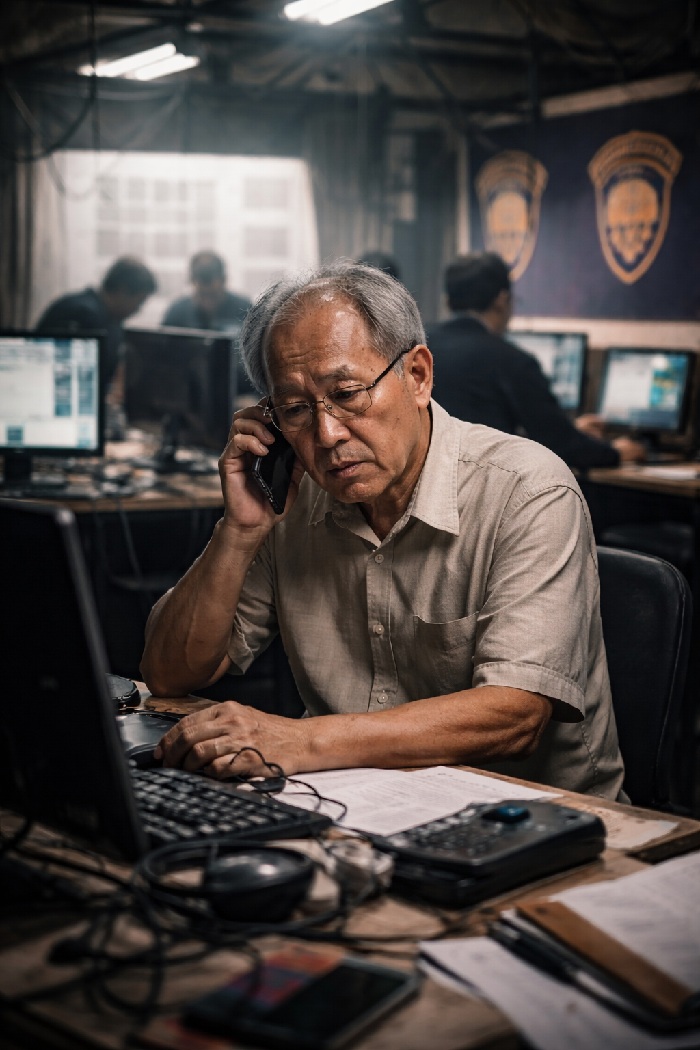

The people who targeted me were not amateurs. They were professionals.

The caller claimed to be THE SCAMMER: FAKE ELECTRICITY COMPANY OFFICER, threatening to cut off my power if I didn’t cooperate. Living alone in the mountains, panic took over. I didn’t send money—but I revealed things I never should have. That mistake was logged, stored, and reused like ammunition.

Inside that compound, rooms were carefully designed to look like Singapore police offices, Australian law enforcement desks, and even a Vietnamese bank branch. Scripts lay everywhere—step-by-step instructions teaching criminals how to impersonate police, utilities, and lovers. This wasn’t random crime. This was industrial-scale deception.

I wasn’t the only one.

Another victim, THE AMERICAN WOMAN — DOMESTIC ABUSE SURVIVOR, had her trauma weaponized against her. Her pain became a tool for manipulation. These criminals didn’t just steal money—they exploited fear, loneliness, and trust.

The scammers operated from a compound known as Royal Hill, leasing space to multiple fraud gangs. One tenant was listed as THE SCAMMER: “ZHANG” (UNRESPONSIVE TENANT), though no one would admit who truly controlled the operation. Everyone hid behind silence.

The place was guarded like a military base. Anti-riot drills. Orders to chase away outsiders. Food delivery banned so no one could look inside. Workers weren’t even allowed to walk shirtless—appearances mattered in hell.

When Thai air strikes hit the area during a border conflict, the criminals fled. More than 100,000 people—many of them trafficked workers forced to scam under threat—escaped similar compounds across Cambodia. Embassies overflowed. Amnesty International called it a humanitarian crisis.

Some of those workers were victims too.

One man, A TRAFFICKED WORKER FROM MADAGASCAR, said his passport was seized, his freedom stolen, and his release only came after bombs started falling. That’s how tightly these scams are protected.

The United States estimates people like me lost $10 billion in 2024 alone to Southeast Asian scam centers. And even when compounds are destroyed, the scammers don’t stop. They shrink, move, and rebuild—again and again.

As a victim, I now know the truth:

This wasn’t just a scam call.

This was organized cyber warfare against ordinary people.

And unless the world treats these fraud factories like the criminal enterprises they are, more lives will be logged, exploited, and discarded—just like mine was.